Sublimation

- ianmcnaughtd

- Dec 22, 2025

- 8 min read

The First Lesson

She dips her chalkduster in water and smears it across the chalkboard.

Us six-year-olds watch the shades of green change in front of us. Ripe avocado peel dissolving back into sunbleached tennis ball.

She writes EVAPORATION where the wetness once was. This is your first formal lesson in alchemy.

A year later, time at school is divided into increments of classes. The sorcery of the water cycle is quartered to science. You’ll see drawings of this phenomenon in posters and textbooks; the ocean, the sun, clouds on a mountain with a river that snakes back to the sea. All bridged with arrows. As you grow older, the drawings become more serious. The smiling face on the sun is the first to go. The clouds get Latin names. New processes appear. Runoff. Transpiration. Sublimation.

Names to remember, orders to follow.

You will be tested on this, you are told.

Condensation – the invisible turning real – becomes part of a five-mark exam question where you need to remember that it comes before precipitation. Pass this test and you get to remember more things, like percolation and plant uptake.

Steadily, mysteries are solved. Groaning thunder, shimmering mirages, flickering stars. All necessary. All sensible.

You’ll learn that a question needs an answer. You'll learn that you'll be rewarded for making sense. You’ll learn that we are irrational beings bent on rationalising. Exchanging the incalculable for explanations. Distilling the abstract incomprehensibilities of love and grief into declarations on tattooed skin. You will be tested on this.

The Cycles

That first lesson of the water cycle is a brush with the ideas of impermanence and immortality. Theoretically opposite, somehow inseparable. It's the unconscious percolation of the idea that everything lives in the grace and grip of cycles.

One of which is the cycle of the womb; the rhythm that writes the arrival of all beings on earth. These maternal revolutions follow an uncanny correspondence to the cadence of the moon – casting shadows on land and spells on seas.

Spasms and convulsions send waves across the world. A language of winds and swells that conducts migration patterns of pods, schools and flocks. It manoeuvres boats packed with ideas, spices and plagues. Stirring Indonesian flotsam with Norwegian jetsam in Patagonian estuaries.

Unmoved by the oscillating swirls on the surface is the deep dark of the ocean. The earth's unconscious that wriggles and squirms with cycles we have yet to whittle into sense.

On the earth's modest helping of land are the courses of scarcity and abundance. Floods blend braided streams as they bring chaos and fertile soil, smothering sins and secrets. Heat fills their absences; draining lakes and bleaching trees anchored in bedrock.

Then there's the meteorological cycles within our minds. Spurts and shortages of chemicals that drive lust-crazed salmon to pick the path of most resistance, instigate teenage hairstyles and initiate the flight plans of the Arctic Tern.

We see the waxing and waning of collective ideas when we band together in groups; the pendulum swinging between desires to share and a need to stockpile. A will for the people to make their own decisions. A wish for those decisions to have been better.

As governors of our selves, we live with the fermentation of former good intentions. We recount the migration of common sense that precedes them. We're still surprised by the seasonal arrival of hindsight afterwards.

A craving for certainty.

A demand for mystery.

Making Ends Meet

The cycle that's the hardest to ignore is the trajectory of the sun. It gives us our daily light that we have sliced into hours – measurable increments to make the almighty manageable.

Time was initially measured out so people could schedule prayers. Then, about 2200 years ago, the Romans made the first public sundial, complete with a standard length of an hour. Time's new, Roman. And we've been in a rush ever since.

Keeping time – once intended as a guideline for rituals – has become an impetus for urgency. We made time then. We serve time now.

Our language reveals this. The way we talk of time is jolted with commercial efficiency: Tax season. Retirement age. The financial year. Quarterly reports.

And within this manner of speaking, there's a fixation on the final result: Get things done. The bottom line. The end-goal. Life expectancy. Projected outcomes. Profits and loss forecast. Make ends meet.

Yet for a society that's obsessed with the final product, we can't stand to talk about death. We stave off the subject with superstitious fervour. All this urgency with an unsaid end. Skirted around and sighed through. Swaddled in platitudes.

This isn't to say that it's wrong to keep time. But there's more to time than human time, with its focus on the finite. The time that nature keeps is a time where it takes thousands of human years for a wind to change or a lake to dry.

Time in a cosmological, geomorphological sense speaks of life cycles instead of lifespans. A life cycle embraces an end so as to reach another beginning. A clock's hands spin in a circle; the liana vine of the Amazon jungle climbs in a spiral – fed by death, feeding by dying.

Between Two Mountains

In the midst of the Sahara Desert lies the Tibesti Mountain Range. Its sheer peaks jut out of the desert’s skyline like plates on a stegosaurus's spine.

These uprisings of volcanic rock have been sharpened by the Harmattan – a wind that blows across north-west Africa to the Gulf of Guinea.

When the Harmattan hits the spires of the Tibesti, a plume of wind peels off the rockface, slides down the slopes and sweeps above the dunes.

The air collides with the bank of the Ennedi Plateau, a sprawl of psychedelic shapes of sandstone that run parallel to the Tibesti Mountains.

This tributary of the Harmattan has now become a new wind, trapped between two outlandishly sculpted mountains. It has nowhere to go but down the escarpment.

The wind picks up speed. Dust billows skywards.

The afternoon sky of the Sahara turns mauve in a haze of airborne sand. The Toubou people turn their heads and wince their eyes as they herd their livestock in the shadows of Tibesti's arches and monoliths.

The wind charges southward, ripping through the sand.

The Sacred Dust

Seven thousand years before this wind was born, these sands were submerged by one of the largest lakes on the planet. Its water spilled over a million square kilometres. An inland sea in the Sahara is as unimaginable today as a desert would have been back then, in an era of North African monsoons.

Over the millennia, the lake had many names. In the time of the Roman Emperor Augustus it was called The Lake Of The Hippopotamus. Scientists talk of it in past tense as Lake Mega-Chad. Its descendant, Lake Chad, is 5% of its former magnitude.

In the Lake Of The Hippopotamus lived microscopic single-celled organisms called diatoms. A diatom possesses a urea cycle, like we do. Their kind has lived in bodies of water on the planet for the past 150 million years. Each diatom lives for around six days.

During their lifespan in the pre-desert Sahara, they would feed off the silicon in the lake while growing a protective shell of silica. Then, they would die and sink to the floor of the seemingly eternal lake.

And so they carried on for thousands of years. Drifting amongst the manatees, microalgae and wild spirulina. Eating, growing and dying – all in less than a week.

As time passed, their environment's heating was set to a gentle simmer. The same forces of evaporation displayed on teachers' chalkboards began to work on the surface of the mega-lake, slurping water vapour up into migrating clouds.

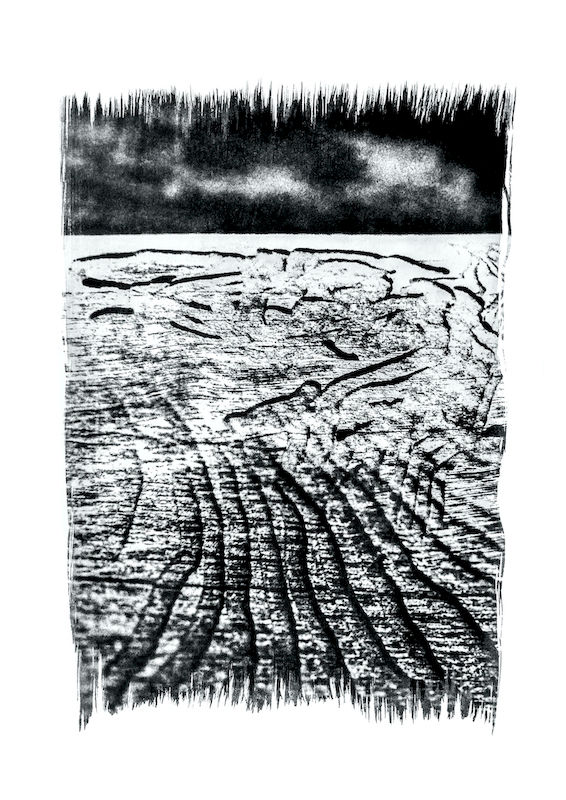

The tide receded. Mud on the banks began to bake and crack. Ribcages emerged in the shallows, turning white and brittle in the sun. The monsoon came late. Packs of striped hyena wandered southwards.

Smaller bodies of water split from the mega-lake, deliriously shuffling off into an ageing savanna. The monsoons stopped coming.

The freshwater sea shrivelled into a lake. Then the lake became an oasis. And then it became the stretch of sunken desert, now called the Bodele Depression.

Today, at the lowest point of Chad, the only evidence of the underwater empire can be found on the scorched desert floor. Here lies 10 000 square kilometres' worth of miniscule shells of long-deceased diatoms, as countless as the stars.

To the north, the wind barrels down the desert.

The Precious Mist

The wind swoops into the Bodele Depression and pounces on the sea of microscopic dried shells. These relics are whipped up like the water vapour years before them. They spiral towards the sun as they swarm in a cloak of dust that sweeps westwards, flinging shadows on the dunes until Africa dissolves into the sea. They drift over the Canary Islands before being scooped into a trade wind.

These ancient drought-surviving diatom shells are rich in phosphorus, and this whirling shroud of them is migrating across an ocean to bring life to countless organisms.

The next landmass is the Amazon River Delta, where the river's artery bursts into the saltwater of the Atlantic Ocean. Beyond lies the Amazon Rainforest, seething with fertility as the southern Sahara once did.

But for all the rainforest's flourishing appearance and elaborate foodchains, most of its roots are grounded in impoverished soil. Here, the earth is so weathered and drained of minerals that it's referred to as a wet desert.

Many plants resort to a diet of dead wood and decaying plant matter to survive; absorbing the minerals of the recently deceased before they seep into the acidic soil. The jungle needs the dead to live.

The cloud's shadow darkens the tangled tributaries of the delta. It starts to rupture from the heat rising off the greenery bursting from the serpentine river. The cloud implodes and starts to rain phosphorus.

This is how the ancient jungle receives 22 000 tonnes of phosphorus every year. From the tiny skeletons of the long-dead an ocean away. Without it, the Amazon rainforest – an immense source of oxygen – would wither.

This magnificent intermingling of cycles and rollicking complexities hinges on the most minute of details. It melts the illusions of the fertile and the desiccated. It’s performed with the theatrics of revolutions; dances of opportunistic air pressure, choreography of flooding and drought. Tales of the barren bringing forth life, and of giving life after death.

This entwining story brings whispers of the sublime. Of wind-chiselled peaks of volcanic rock, of memories of dead lakes and the might of the ghosts of one-celled bodies.

Two Thirds and Three Quarters

After learning the labels on the water cycle poster, you learn about the water around you. In biology class you're taught that 60% of an adult human is made up of water. Geography tells you that water covers almost three quarters of the planet.

Sometimes it occurs to me that I – and anyone else living on one of the planet's blotches of temporarily dry soil – am more water than anything else. Leaking, steaming, damming, fermenting. And that to stay alive is to take in particles of water that precede you, that outlive you.

These invisible marriages of hydrogen and oxygen have been shared amongst living beings ever since oceans existed. To survive is to take in traces of life beyond our lifespans.

By virtue of living, you are porous to the possibility that you could consume particles of the sweat of Ghengis Khan's horses and ingest slivers of the iceberg that mangled the ship that God couldn't sink.

For a moment – in the water that comprises two thirds of you – you could contain remnants of the barbicide of Lee Harvey Oswald's barber.

Your blood plasma carries distillations of the Ganges River that flows from frozen mountains to humid seas, caressing its offerings along the way.

It will be drawn through your bones where it will curdle with your marrow, mixing with the dregs of a six-year-old's unsuccessful attempt to recreate an evaporation experiment in the latter twentieth century.

There's a chance that within the sum of your parts is one part amniotic fluid of a Mesopotamian concubine, one part trickle from Shaka Zulu's tear duct. Unnumbered parts of unnamed lovers' saliva.

The ink of an unsent letter of apology. Smears of ochre pigment and blood coagulating on a cave wall. Meltwater from the Ice Age. Instant coffee consumed by a puppeteer on the set of the 1993 movie Jurassic Park.

How will we remind ourselves about this? Of these arcs beyond our attention spans, of these spirals beyond our lifespans.

How do we consider the untold histories of the shapeshifting particles that move through us? Unnoticed. Unrelenting. Until the sun explodes.

Discuss for five marks.